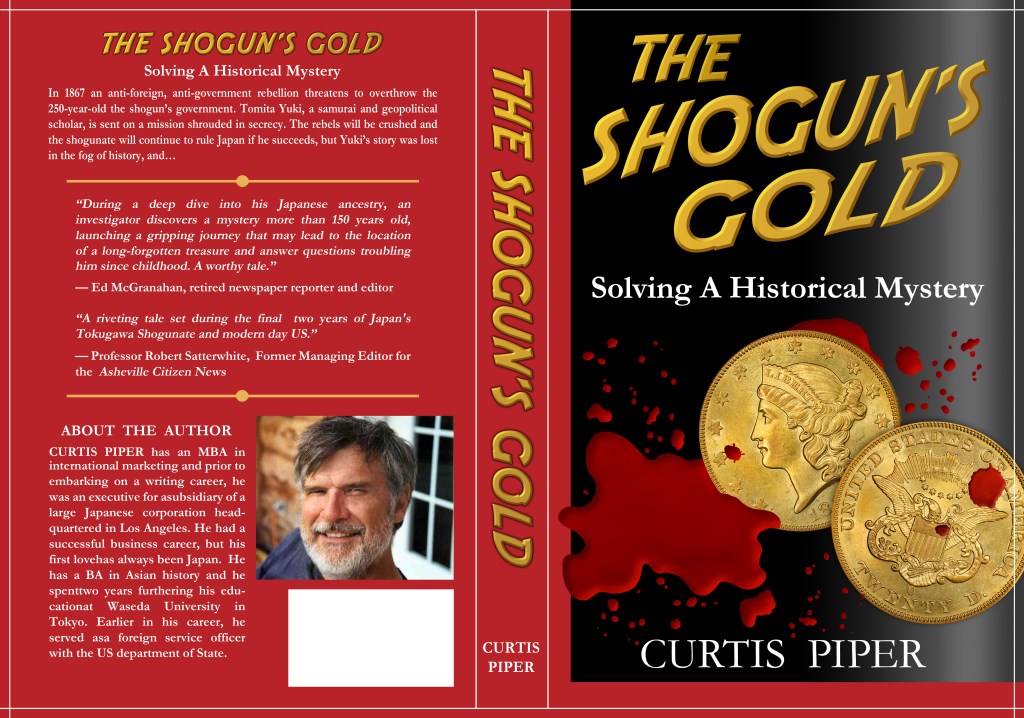

THE SHOGUN’S GOLD–Solving a Historical Mystery….Second Edition!

My wife and I went to the owl cafe in 2022 and 2024. I read that only two are in existence. One is in Fukuoka, and one in Tokyo. Since we were visiting my “Japanese Mama” in Fukuoka, we went there. There were about fifty owls. A couple were in cages, but most were perched on shelves around the cafe. In order to stay and meet the owls, we were required to buy a couple cups of coffee for about $18 apiece.

The cafe is divided into two areas. When we entered and paid, we sat where we could drink and look at the far wall where there were a couple of owls. Each chair had a small table, but more about that later. The second area has a large wall where numerous owls are perched. Small signs describe the owls and indicates if they can be touched or stroked. The manager also helped us to use our forearms to encourage certain owls to perch on them.

My wife petting an owl in 2022.

The Shogun’s Gold-Solving a Historical Mystery

Characters

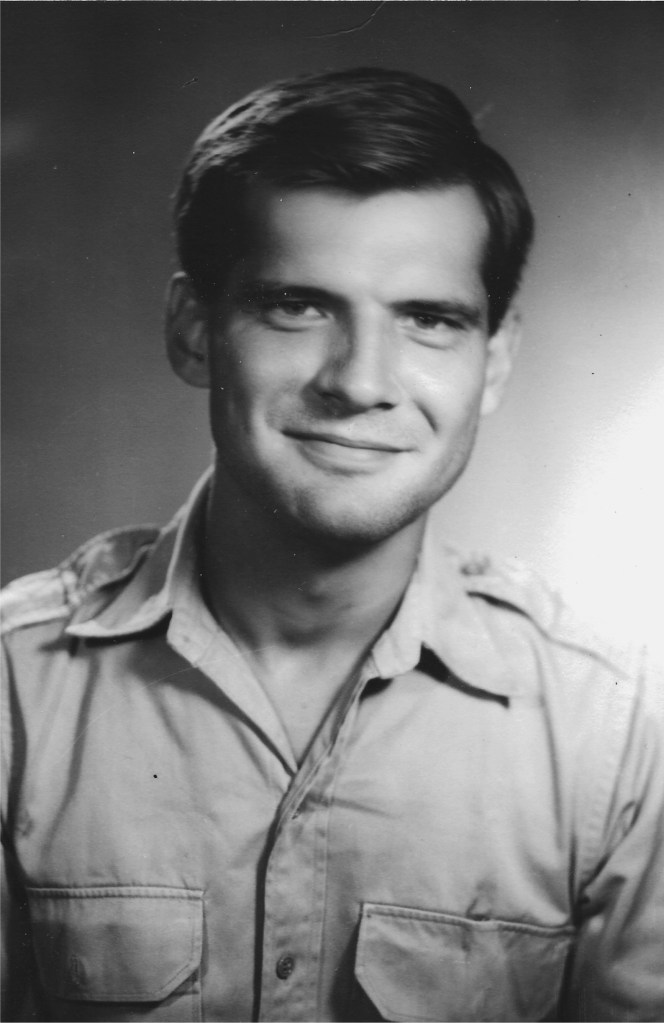

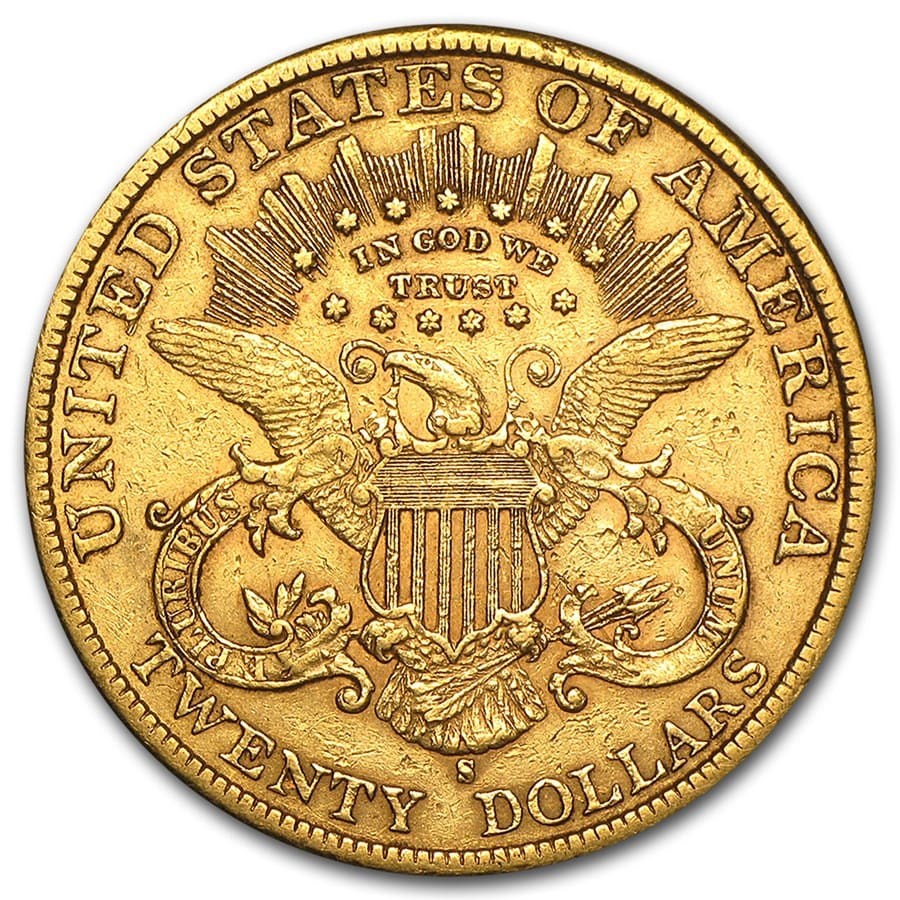

The book starts out in a hot attic in South Pasadena, California. Parker West seen below, is an insurance fraud investigator. After jogging a 10K, he retreats to his deceased parents’ attic where he finds some puzzeling items in an old trunk. Parker searches the trunk and is surprised to find a gold coin. He googles it and learns it is valued at over $300,000!

It is called a $20 double eagle despite the fact there is only one eagle on the reverse side of the coin. The reason? It is double the American $10 gold eagle.

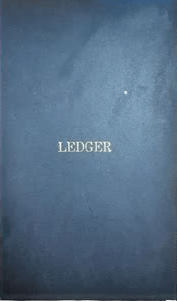

Parker also found a wakizashi, a small Japanese sword, an old rifle, and what appears to be an American ledger. He opened the ledger, expecting to find colums of numbers. Instead, he found a lot of Japanese writing.

TO BE CONTINUED…..

It took several years and a lot of you-know-what.

Hint: Paper & Ink, travel to Japan, proofreading, cover design, and professional book formatting all added up.

But it was all worth it.

What the book is about

In 1868, a massive cache of government gold supposedly disappeared from Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s castle. The shōgun’s finance minister reportedly removed the treasure and buried it in northern Japan to keep it out of the hands of the advancing anti-shōgun rebels.

Historians claim the cache never existed. But concurrent with the disappearance of the gold, Tomita Yuki, a loyalist samurai, and Avery Butler, a retired American Union Army officer, embark on a secret mission with almost a ton of gold. But their mission ends in a disaster. Tomita is forced to return to Japan without the gold, and his story is lost in the fog of Japan’s civil war. Betrayal and bloodshed threaten to bury Tomita’s legacy along with the treasure, but love and devotion will not have it.

Over 150 years later, Parker West, a private investigator, discovers a Japanese diary in his parents’ attic. Jason Tanaka, a historian, translates it, and doing so almost costs them their lives. Their search takes them to many places, and genealogy helps them unravel the mystery, as does kanji, or written Japanese.

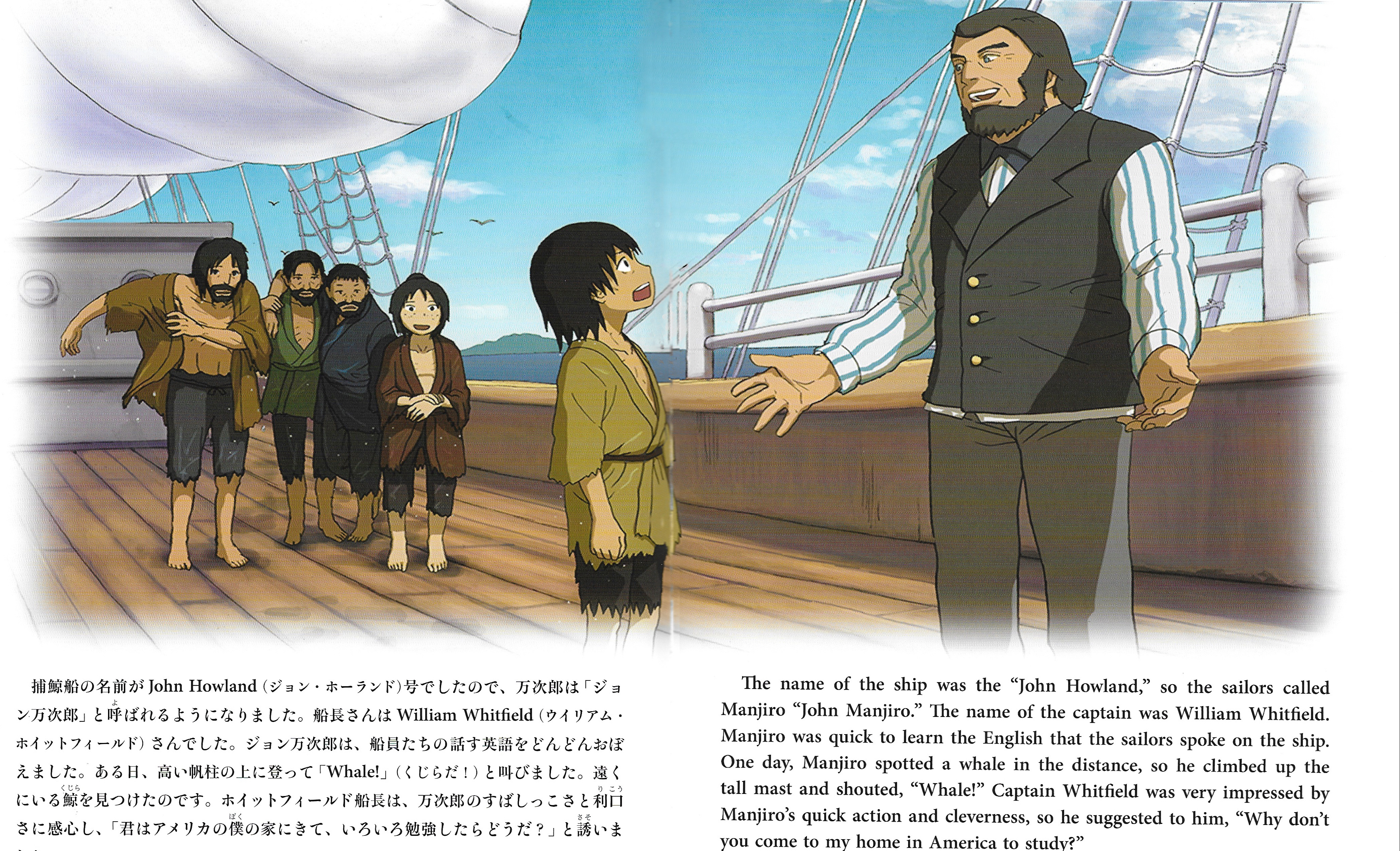

The novel shares fascinating information about the little-known tragedy involving nineteen teenage samurai, Bushido, the way of the warrior, and John Manjiro, the fourteen-year-old ship-wrecked boy who was the first Japanese to visit and live in America.

The book may be purchased on Amazon in scores of countries. It is also available in Kindle.

Go to AMAZON and type in: The Shogun’s Gold: Piper

It was not uncommon for samurai to commit ritual suicide called seppuku “belly slitting”. Harakiri is another term, often mispronounced as “Hairy Carry”. It was a death ritual that samurai employed to show their sincere regret for having failed in their obligations. Slitting one’s own throat was another method.

One of the most compelling accounts in my novel, The Shogun’s Gold-Solving a Historical Mystery describes the true story of a horrific mass suicide of nineteen teenage samurai. The incident is relatively unknown outside of Japan, but it plays an important part in my novel. It occurred at the end of a short civil war between those who supported the Shogun and the Imperial Army which sought to“restore” the Japanese emperor.

In 1868, the northern domain of Aizu was besieged by the Imperial Army which surrounded and bombarded Tsuruga Castle which was located in the center of the Aizu’s capital. It was thought to be impregnable, but it was no match for the modern English cannonry employed by the Imperial Army. While the castle was being bombarded, another battle was taking place miles away.

A contingent of teenage samurai, part of the Byakkotai, or “White Tiger Force” was sent to take part in the battle, but the teenagers became lost. The leader decided to return to the castle to aid in its defense, and the small group stopped on a hillside clearing where, in the distance, they saw the castle town enveloped in smoke and flame. They assumed that they were too late to come to the capital’s defense and they all decided to commit suicide to atone for their perceived failure in defending Aizu.

This tragedy is graphically described in The Shogun’s Gold when the hero of my novel stumbles upon the bodies of nineteen boys whose ages ranged from 16 to 17. Here is a modern woodblock print depicting the incident.

In present day Japan, suicides average 70 per day and teenage suicides are notably high. Failing exams in school is one of the main reasons why Japanese youth take their own lives.

Another, more famous case of mass suicide has been immortalized in the play, the Story of the Forty-seven Samurai. However, from my point of view, the tragedy of the Byakkotai is more compelling because those who died by their own hands were so young.

In 1984, NHK, the national TV network broadcast a serial depicting the end of the civil war in Japan. You may find it on YouTube.

When Japan joined Nazi Germany and Italy before the outbreak of WWII, Mussolini sent his foreign minister (his son-in-law) to Japan to donate part of an ancient Roman column to memorialize the Byakkotai sacrifice. Hitler sent a large, stone tablet featuring a large swastika that was chiseled off after the war.

ABOUT JAPANESE PLUMS and PLUM TREES

I took the above photo at Suzumushi Temple in Kyoto in 2017. (Suzumushi is a kind of insect called a “bell ringing cricket”…but, that’s a whole different story!)

Plum in Japanese is “ume”, written 梅. The left side of the character 木 is a pictograph for tree and the more complicated right side provides the reader with the on-yomi, or Chinese pronunciation. The plum is one of the favorite trees in China and Korea and Japan. It is regarded as the harbinger of Spring. It can have red, white, or even yellow blossoms. It is closely related to the apricot. There are several varieties found in Japan.

The fruit ripens in June and July during the rainy season, and the word for rainy season is “bai u” which means “plum rain” 梅雨. Oh, how hot and muggy it is in Japan during bai u!

The flower is a favorite family crest, and there are scores of variations. One is pictured here—-

Plum wine is a favorite in Japan and many housewives brew it. They take a big jar, fill it with plums and shōchu, a Japanese liquor. However, it is not uncommon for them to use vodka. The jar is kept in a closet where the liquor slowly absorbs the flavors of the plum fruit. Ume boshi, or salted (pickled) plums are a favorite condiment.

There is a saying in Japanese:

“Sakura kiru baka ume kiranu baka.” It literally means “It’s stupid to trim a cherry tree, and its stupid not to trim a plum tree.” The reason being that cherry trees do not do well when they are pruned.

The following site contains a lot more information about ume. It’s a great site if you like things Japanese.

https://www.kyuhoshi.com/2015/01/01/plum-ume-blossom-in-japan/

New Year’s Day is the biggest holiday of the year in Japan. It used to coincide with the Chinese New Year, but that is another story. It is a time for gift giving, celebrations, feasting, and visiting one’s ancestral grave sites. On New Year’s Eve, millions of Japanese visit their local Shinto Shrines and Buddhist temples. Temple bells toll 108 times. It is believed that humans have that many “passions” or sins. Each strike of the bell supposedly drives away one such passion.

About a week before January first, people start their “Big Cleaning”. Students scrub the floors of their schools and dust every nook and cranny. Employees do the same at their work sites. Public parks, the road in front of one’s home, and one’s garden get the clean treatment too. It is very important to start the new year out in clean surroundings. In Japan, cleanliness is indeed next to Godliness!

From left to right, photos courtesy of:

https://japonismo.com/blog/el-osoji-o-la-limpieza-de-fin-de-ano

http://cantinho-coreia.blogspot.com/2013/12/o-costume-do-osoji-grande-limpeza-de.html

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2015/12/26/lifestyle/osoji-ways-keep-home-spick-span/#.WF0qOLG-K8U

One of the traditional foods served on the eve of the hibernal, or winter solstice 冬至 is the Japanese squash called kabocha. This squash is harvested in the fall and allowed to “rest” outside in the cool air where its flesh sweetens with age. My wife served a really tasty kabocha dish on the 20th of December. It goes with just about any meal from steaks to mac ‘n cheese! They are found in most supermarkets. Here is how to prepare it—-Enjoy!

1.Wash the skin, cut in half and scrape out the seeds.

2. Make slices about a quarter inch thick, leaving the skin on.

3. Heat a frying pan under slow heat and add about a tablespoon of olive oil. Fry on both sides until the orange meat is tender. Add salt and pepper.

Another recipe that is strictly Japanese style is as follows:

- Slice the squash into one and a half inch cubes. Again, leave the skin on. It’s good!

- Add to a deep pan: 1 cup of water (or dashi, if you have it), 2 tablespoons of sugar, 2 tablespoons of mirin (sweetened sake), 2 tablespoons of sake and 2 tablespoons of soy sauce. You probably have soy sauce. But, if you don’t have the other ingredients, just replace with water. (Some people have suggested chicken broth, but we’ve never tried it.)

- Bring to a boil and add squash. Gently cover with pre-cut tin foil, the size of the inside of the pan with a nickle sized hole in the middle

- Turn to low heat and cook until the meat is soft. Use a tooth pick to test whether its done.

Japanese companies often rely on unqualified employees to translate ads, menus, instructions, etc. into English. The results are often mystifying. I found this example in The Economist:

SUPER FUN WARNING!

Many big grinding comes with being fun too close on grid of power! For ease of honor, find early the grand gateway much closer to away. Much regards please.

We can only wonder!

An excerpt from the draft of my novel The Shogun’s Gold-Solving a Historical Mysery:

“Gentlemen, I am Major Benjamin Butler, retired. I have come to your estimable country well recommended by Mr. John Manjiro.”

Just who was the man named Manjiro? He was a historical figure born in Japan in 1827. “Commoners” did not have family names. At the age of 14 and desperately poor, he set out with this uncle and friends to fish off the coast of Shikoku Island. A violent storm swept them away, and they ended up shipwrecked on the deserted island of Torishima, about 700 miles from their home.

They were stranded there for several months and were at the point of starvation when an American whaling ship stopped and rescued them. The kindly captain, William Whi tfield, clothed and fed the ragged shipwrecked fishermen and took a shine to Manjiro, offering him the chance to return to the U.S. with him. To this, John Manjiro, as Whitfield re-named him, readily agreed. When he landed in Fairhaven, Massachusetts in 1843, Captain Whitfield saw to it that John learned English at the local public school.

tfield, clothed and fed the ragged shipwrecked fishermen and took a shine to Manjiro, offering him the chance to return to the U.S. with him. To this, John Manjiro, as Whitfield re-named him, readily agreed. When he landed in Fairhaven, Massachusetts in 1843, Captain Whitfield saw to it that John learned English at the local public school.

Manjiro eventually entered the Bartlett School in Fairhaven where he learned navigation and advanced mathematics. He signed on to a whaling ship and was promoted to harpooner. After a lengthy voyage, he returned to Fairhaven… but not for long. With the $350 he had earned, he sailed to San Francisco and then travelled to the Sierras where he panned for gold and came back with $600, about $30,000 in today’s money.

Homesick, he made up his mind to return to Japan. Doing so was a dangerous proposition because the shogun’s government policy of national isolation made it a capital offense to have contact with foreigners. Nevertheless, John Manjiro booked passage on a ship that took him and several of his former shipwrecked mates to Okinawa where he was, for all intents and purposes, put under hous e arrest.

e arrest.

After months of interrogation, he was allowed to return to his home where he met his widowed mother after almost 12 years. In 1853, the Shogun’s government summoned him to Edo (modern day Tokyo) where he advised the government on matters concerning the treaty demands being made by Commodore Mathew Calbraith Perry who had arrived with a flotilla of warships. For his services, Manjiro was elevated to the rank of samurai. He chose Nakahama as his surname after the town where he had been born.

In the ensuing years Nakahama Manjiro helped establish the whaling industry in Japan, translated a book on navigation, and acted as an official interpreter when the first Japanese delegation visited the U.S. But, he never forgot the kindness of Captain William Whitfield and in 1870, when he landed in New York with a government delegation, he travelled to New Bedford, Massachusetts to visit his old friend and benefactor. A photograph of the two men was recently discovered at the New Bedford library and is pictured here with the library’s permission.

Returning to Japan, he became English professor at the institution which would eventually become Tokyo University. He died in 1898 after a long illness.

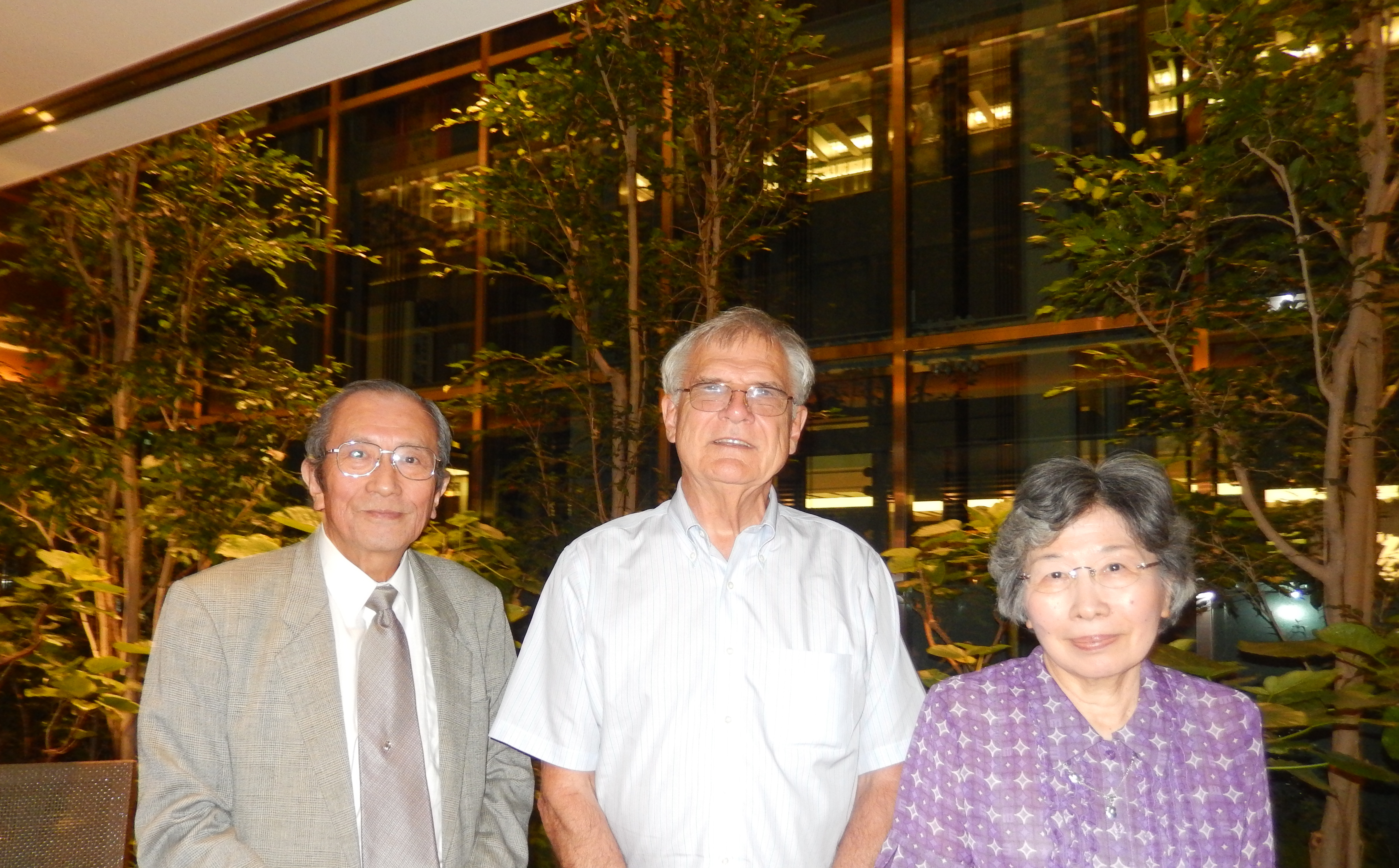

Several years ago, I made trips to  Japan to conduct research for my novel “The Shogun’s Gold-Solving a Historical Mystery.” During one stay, I had the pleasure meeting and interviewing Dr. Issei Imanaga, a descendant of Manjiro. He and his wife Yuko provided me with much valuable information for my novel. Since then, we have become close friends.

Japan to conduct research for my novel “The Shogun’s Gold-Solving a Historical Mystery.” During one stay, I had the pleasure meeting and interviewing Dr. Issei Imanaga, a descendant of Manjiro. He and his wife Yuko provided me with much valuable information for my novel. Since then, we have become close friends.

In 2009, a Japanese philanthropist bought Captain Whitfield’s home in Fairhaven and turned it into a museum which is now operated by The Whitfield-Manjiro Friendship Society. Every other year in October, a festival honoring Whitfield and Manjiro is held in Fairhaven. The festivals are now on hold until the Covid pandemic runs its course. Check the following website from time to time to find out about the timing of the next festival:

http://www.whitfield-manjiro.org/THE_MANJIRO_STORY.html